05/02/2010

Key themes of the Noughties

Private equity muscles its way in

The Noughties saw an unprecedented level of interest by private equity players in the sector. Size definitely mattered: Tommy Hilfiger ($1.5 billion), Barneys, ($942 million), Neiman Marcus ($2.6 billion), Valentino Fashion Group (€2.6 billion) were amongst the biggest deals of the decade and all ended up in private equity portfolios. One of the most talked about success stories of the period, Jimmy Choo, changed private equity hands three times. The record multiples paid on some of these transactions were underpinned by the willingness of private equity owners to leverage their investments to the hilt, driven by benign debt market conditions and the expectation of endless growth potential.

Signs that things had gone too far emerged in 2007, when industry buyers effectively withdrew from the M&A game, stating that they could not compete with the multiples paid by the private equity world. The credit crunch robbed the private equity market of its financial muscle and the bigger players’ interest in luxury goods deflated faster than a bodybuilder coming off steroids. Smaller, specialist players are still active in the sector although more on the hunt for bargains or financial distress situations. A less crowded market is also making room for family-backed investment vehicles, generally with longer term investment horizons and an appetite for luxury and brand assets.

Watchmania: consolidation and roller-coaster ride

The beginning of the Noughties witnessed a goldrush for watch brands by the larger players in the sector.

LVMH started the trend at the end of 1999 with the quasi-simultaneous acquisitions of Tag Heuer, Ebel, Chaumet and Zenith and the creation of a Watch & Jewellery division. Prowling from the sidelines, Swatch Group snatched Breguet and its famed manufacture, Lémania. Gucci Group also invested in the sector, buying back its watch license and investing successively in Boucheron and Bedat in 2000. Sector consolidation hit fever pitch that same year when LMH (the Mannesman-owned holding company of Jaeger-leCoultre, IWC and Lange & Soehne) was sold for a reported 9x sales to Richemont, who attributed the record-breaking multiple to LMH’s manufacturing capabilities and the potential of its brands, but who in reality was paying for the leadership of the premium segment in the industry.

Most of these brands received significant investment in the lean couple of years after 9/11, and when optimism returned to the luxury goods market the watch sector benefitted disproportionately relative to other product categories. It embarked on its wildest bull run in recent history, fuelled by the boom in the financial services industry and the rise of emerging markets such as China and Russia. Watches grew in size and started to showcase ever more numerous complications. This made for a particularly harsh landing when the sub-prime crisis unfolded. Retailers, petrified at being caught with too much inventory, stopped buying altogether and the watch market went into a painful eighteen-month apnea. There are however signs of life at the turn of the decade with trade inventories being reconstituted, a sure sign of market confidence.

Turn of fortune for designers?

The Noughties started out with Tom Ford embodying the star designer, the all-powerful sun king of the luxury sector, whose creative talents had propelled Gucci from an also-ran to the hottest and sexiest brand in the world. Throughout the sector, designers shared in the limelight, their exploits having outgrown specialist trade magazines and now being played out by mainstream media. Their compensation packages started to outshine even Wall Street, as industry bosses, having taken on board the need to empower the creative forces in their businesses, competed to attract and retain talent. Every top designer demanded their own brand, and the investment to go with it, alongside their role as the creative director of a large established luxury brand.

Then something gradually happened that changed the mood of the market. Tom Ford left Gucci, his absolute requests for control, power and money having proven too much for his PPR bosses. Star designers’ own brands, backed by considerable investment with the promise of great things to come, somehow failed to deliver. Alexander McQueen and Stella McCartney’s eponymous businesses were the last two to receive significant investment before the industry started to question the model. The list is impressive.

Liz Claiborne gave back to Narcisco Rodriguez the business it had bought from him a few

years earlier. Hedin Sliming, having walked out of Dior Homme with a view to launch his own brand, failed to find a backer. Phoebe Philo joined LVMH-owned Céline despite having initially set her sights on building her own brand. Even Puma recently “sold” back Hussein Chalayan his own business.

The rise of the contemporary designer

Whilst the traditional high fashion main line business was getting the equivalent of the industry cold shoulder – with the remarkable exception of Lanvin, where the creative and commercial talents of Alber Elbaz were performing miracles – some new designers turned up who were happy to design to a price point and to a margin while still fully expressing themselves. What had happened in bags earlier in the decade with the rise of the contemporary category (Isabella Fiore, Kooba, Botkier) was now taking place in fashion with the likes of Philip Lim and Alexander Wang. The size of contemporary floors grew along with the offering and became more mainstream, offering customers new and interesting “designer-feel” brands which were significantly cheaper than established designer brands. This was also reflected at retail level with the successful development, at price points below traditional designer level, of brands with a broad enough offering to justify their own retail, often across several categories, like Tory Burch.

This in turn lead top designers to focus on the category; none more successfully so than Marc Jacobs with his Marc by Marc line.

The blurring of boundaries between luxury and lifestyle through design

One of the defining stories of the decade was the transformation of PPR from a builders merchant and retail group to a luxury and lifestyle group. First came the contentious battle for Gucci Group, which saw PPR commit to launch a fully-priced takeover offer on the eve of the 9/11 attacks. A few years later, having not been able – or willing – to buy a large enough target in luxury goods to challenge the leadership of LVMH and Richemont, it surprised the market by announcing the acquisition of sports and lifestyle group Puma, having spent the best part of €10 billion between the two deals.

The notion that the boundaries between luxury and lifestyle were starting to blur was further augmented by the multitude of collaborations between designers and high street chains over the decade (H&M collaborations with Lagerfeld, Victor & Rolf, Stella McCartney & Matthew Williamson; Target with an endless list of American designers, and more recently Jil Sander for Uniqlo).

We think that this blurring of boundaries between luxury and lifestyle has occurred through, simply put, the growing importance of design in every consumer business, across price points and categories.

The same importance of design is now prevalent at the volume end of the market. If speciality chains were a product of the 80’s and 90’s, there is no doubt that the Noughties saw an astonishing rise in the development and success of accessibly-priced models: Zara, H&M, Uniqlo or, in a different category, Coach. Be they different concepts, they all offer fun and interesting products at a very accessible price point, some with their own design ethos and some by riding the mood and ideas of the moment and bringing constant newness.

Death of a marketing manager

Whereas marketing had traditionally been the favoured career track for consumer businesses, the growing importance of design and creativity changed things there too. Luxury goods companies began to cultivate and reward those of their employees and associates who were able to bridge the gap and work intelligently with the design and production teams on the one hand, and the commercial people on the other hand.

Such associates had to be nimble and sensitive enough to understand and harness creative emotions and to work with products. Budgets and market forecasts, while necessary, started to take a back seat in the discussions. Marketing became lumped in together with sales. No more “designing to a brief from the marketing team”, but in its place successful brands have a more collaborative process, with a merchandising type interfacing with a tripod consisting of the design, production and marketing sales functions. The marketing king is dead, long live the merchandising king!

What lies ahead

The luxury sector is embarking on a new decade with an assured yet uneasy footing. It has cut costs and restructured, but while there are rich pickings in the East, traditional developed markets are flattish. The need to offer real value to customers, either in the form of reduced pricing or outstanding quality, is a driving force.

Yet traditional models of doing business are cracking up. The high-end fashion designers model has been left by the side of the road. Once offering the promise of rapid, capital-free wholesale growth, department stores are moribund and make no-one happy: not the customers who are bored, not the brands who now find it very hard to make money in such an environment. New ways of doing business for luxury brands,new business models, will be formed in the next decade.

What will they entail? Creativity, for sure. Some vertical integration for the brands who want to protect the integrity of their supply chain. We have already witnessed this trend in watches, specialist skills for couture and high fashion, and the sourcing of exotic skins. Some will go local (like Hermès with Shang Xia). But we think fortunes will be built on rethinking distribution in the sector. It has to happen – current models don’t really work anymore. The web hasn’t played to its full strength in the sector. That will be one key. The search is on for the others…

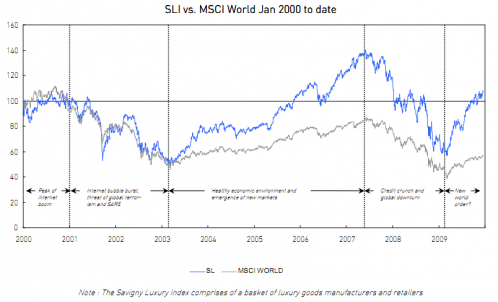

The SLI began 2010 pretty much at the same level as it started 2000. This is a lot more than can be said for the general market index (we have moved to the Morgan Stanley Country Index for the World or MSCI World), which experienced a 43% decline over the same period. The Noughties have been a tumultuous decade during which we have witnessed two substantial market corrections, the worst terrorist act in history as well as both a period of unprecedented consumption and deep recession. All in all not an easy market environment to operate in!

2001 – 2003: we thought it was all over then…

The beginning of the Noughties saw the first big market correction, following the longest stock market bull run in history. The correction began with the bursting of the internet bubble, but took a turn for the worse following the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center and ensuing global political instability. The threat of SARS added insult to injury causing a further drop in international tourism, a key driver of luxury goods sales. The SLI tumbled 55% from its peak in August 2000 to a low for the decade just a few days before the launch of the invasion of Iraq in March 2003. The main issue that emerged in this period was the sector’s dependence on tourist dollars, particularly Japanese, prompting many groups to strengthen their retail footprint in Japan.

2003 – 2007: the golden age of Richistan

The second leg of the Noughties saw a return to the golden age of luxury goods, driven by an improving global economy, favourable exchange rate movements, the emergence of new markets as well as a substantial increase in the number of high net worth individuals. The SLI shot up 195% from its low in 2003 to its peak in mid-2007: it rose sharply in 2003 following the invasion of Iraq and end of the SARS scare and again in the second half of 2005 and 2006, backed by strong economic data from emerging luxury markets. This was the era of bling when the world seemed to be composed of haves and have yachts: luxury brands couldn’t produce “exclusive” statement pieces fast enough, and they started a race to open distribution in newly wealthy markets across the globe.

2007 – 2009: a house of cards

Signs of trouble emerged in 2006 when the US sub-prime mortgage market began to falter. Things

definitely took a turn for the worse in the second half of the year and the term “credit crunch” became a household name. By mid 2007 there were rising concerns that the global economy was going to take a turn for the worse and that stock markets were overheating. The SLI peaked during this period and the multiples of its constituents became hard to justify on the basis of their fundamentals. Nevertheless, few foretold the severity of the impending financial crisis. The first really big tumble took place in the run-up to the crucial Christmas trading period, reflecting uncertainty as to the sector’s resilience, causing the SLI to fall 31% between October 2007 and January 2008. What followed was a period of increasing volatility, marked by sharp upturns and even steeper falls as the world went into financial meltdown. The SLI fell off a cliff in two stages: first to fall in the first half of 2008 were stocks exposed to affordable luxury and/or with a weak presence in emerging markets, resulting in a drop of 23% in the SLI from May to July; in the autumn virtually no stock was spared as the true scale of the financial crisis came to light and the SLI tumbled a further 42% between September and November. All suffered, but the watch sector in particular was exposed for its quasi exclusive reliance on wholesale distribution channels, which led to apocalyptic inventory destocking during the downturn. The overall response of the luxury goods industry to this downturn was swift and decisive: costs were controlled, capex was cut across the board and conglomerates focused on their strongest brands.

2009: the year the SLI earned its stripes

2008 Christmas trading was a bloodbath for retailers but a shopper’s paradise for consumers willing to part with their precious dollars. Heavy discounting was the name of the game as all players tried to shift excess inventory. The rest of the year felt generally miserable, with the only good news coming from China where growth resumed after a hesitant first quarter. On the stockmarket front, both the SLI and the general market index benefitted from market perception that corporates had taken the appropriate cost-cutting measures. The upward trend of the SLI accelerated in the second half as a result of the restart of the Chinese growth tractor and the general feeling that the bottom of the crisis was behind, resulting in a gain of 21% for the year.

Outlook: measured optimism

2010 will be an interesting year for the luxury goods sector. Consumer sentiment has shifted away from ostentatious consumption. “Value” has been redefined, benefitting both accessibly-priced business models and those focusing on expensive, timeless classics. The nimble and light-footed survived, while industry leaders reinforced their positions and gained market share.

The good news is that the sector as a whole will continue to grow and is likely to outperform the global economy on a long term basis. But a new world order remains to be found. Traditional luxury markets have been turned upside down, with new geographies taking over. Traditional distribution models have been mortally wounded, with department stores taking a direct hit. Creative strength, differentiation, customer relationship will be key. Finding the right distribution strategy will be essential. Watch this space….

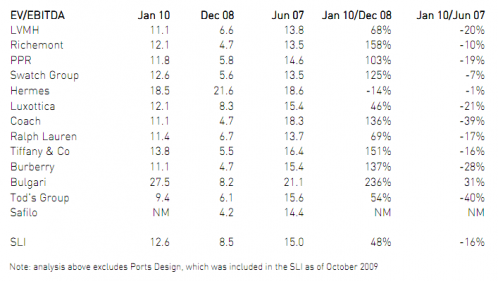

A tighter range of multiples

Two things happened to sector valuations during 2009.

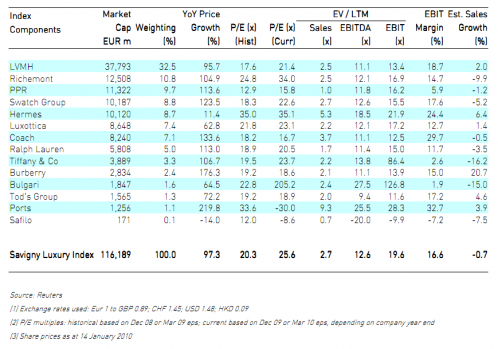

Unsurprisingly, valuation multiples went up substantially, rising 48% for the SLI as a whole to an average of 12.6x EBITDA as at January 2010. This compares to a peak of 15.0x in mid-2007.

Secondly, the range of multiples narrowed quite significantly. Most individual stocks are now trading in a tight range, between 11x and 12x, in contrast to a year ago, when multiples ranged from 4x to 8x. The reason for this narrowing of the range of EBITDA multiples is not obvious. With some notable exceptions (Hermès, Bulgari), it seems that the market is still looking for the tools to determine the appropriate value of each individual stock, and is applying a “default” valuation multiple of 11-12x for the sector as a whole.

Surely this should enable the savvy, well-informed investor to take advantage of this cloud effect and pick the winners of the pack. You read it first here!

Important Notice

This newsletter is distributed from time to time to clients and contacts of Savigny Partners LLP (“Savigny”) who are interested and professionally experienced in the luxury goods sector. The views and opinions expressed in this newsletter pertain to themes that are topical to the luxury goods sector as at the date of this newsletter, and are meant to stimulate open discussion between Savigny and its clients and contacts. The information in this newsletter has been compiled from sources believed to be reliable but neither Savigny, nor any of its partners, officers or employees makes any representations as to its completeness or accuracy. This newsletter is not intended to help its addressees or readers make investment decisions, nor does it purport to make recommendations regarding potential investment decisions. Savigny shall not be liable or responsible for any loss or damage caused by or arising from any reader’s reliance on information contained in this newsletter. Please note that some or all of the brands, and the companies

which own brands, mentioned in this newsletter may have been and may continue to be clients of Savigny or may have a professional relationship with Savigny.

M&A activity in the sector

Companies that have changed ownership or received investment in 2009

- Father and son private investors Hans-Jochem and Hannes Steim acquired Junghans Uhren, the

German watch and clock maker, for an undisclosed consideration in January - KPS Capital Partners acquired the substantially all of the business of crystal and tableware group Waterford Wedgwood in an asset transaction in March

- Private equity firm Castanea Partners acquired niche cosmetics brand Urban Decay in March

- Private equity firm Patriarch Partners LLC acquired Stila Corp, the American make-up brand in April

- LVMH acquired a minority stake in the ethical clothing company Edun in May

- The management team of Cruise, the UK-based luxury retailer, acquired the company in May

- NEO Capital backed a management buyout transaction of Alain Mikli International, the luxury optical frame designer, for an undisclosed consideration in May

- Emerisque Brands, together with S. Kumars Nationwide, acquired Hartmarx Corporation, the US-based producer and marketer of casual apparel for a consideration of $119 million in August

- Broadwick Group, owner of Jaeger, acquired English Apparel brand Aquascutum, for an undisclosed consideration in September

- The Hong Kong-based company Sincere Holdings acquired Sincere Watch, the Singapore-based

company engaged in the business of watch and clock retailing, for $80 million in September - The Gaydoul Group, the Swiss family holding company, announced the acquisition of stockings and lingerie company Fogal in October

- Steiner Leisure announced the acquisition of the spa and skincare company Bliss World Holdings for a cash consideration of $100 million in November

- Endurance Capital acquired Primera, the women’s apparel manufacturer and retailer (Apriori, Cavita, and Laurel), from Escada for an undisclosed consideration in November

- A private family trust acquired a 12.5% stake in French fashion house Lanvin for an undisclosed amount in November

- Kwiat Enterprises, Triton Equity Partners and Och-Ziff Capital Management Group acquired Fred Leighton, the American jewellery maker in November

- Greenwill, the holding company of Italian leather goods company Tivoli, acquired British luxury leather goods and stationery retailer Smythson for a total consideration of £18 million in December

- The Mittal family acquired German fashion group Escada for an undisclosed consideration in December

- The Edmond de Rothschild LBO Fund acquired a majority stake in the French interior design company Christian Liaigre for an undisclosed consideration in December

- The Aquila family acquired 90% of Montegrappa 1912, the Italian pen manufacturer from Richemont for an undisclosed consideration in December

- Alain Mikli International acquired a 75% stake in Sporoptic Pouilloux, the manufacturer of Vuarnet sunglasses, for approximately €4 million in December

- Dutch investment company HAL Holding waived all remaining acceptance conditions and started its full restructuring of Safilo Group in December, which is expected to be completed by the first quarter of 2010