19/10/2009

Fragrances – the essence of a good brand?

Luxury brands have long appreciated the potential to capitalise on their brand cachet by marketing fragrances under their name to a wider public than their core customers, thus providing a healthy stream of cash flows and providing a “window into the brand” for new customers. The rewards of hitting a winning formula are substantial, as witnessed by the perennial success of Chanel no.5 (launched in 1921) and Eau Sauvage (launched in 1966), to name a few. The problems began when every Tom, Dick and Britney wanted to join the party, resulting in an overcrowded market with upwards of four hundred new fragrance launches per year, compared to fifty a couple of decades ago. Brands have had to shout louder in order to get their fragrances noticed, investing in high profile advertising campaigns, celebrity endorsements and lavish launch parties, all of this for a one-in-four chance of their fragrance surviving more than two years and where a fragrance is now deemed successful if it manages to capture 2% of the market. There also has been considerable pricing pressure in the overall designer scent segment resulting in a wider distribution of perfumes in order to achieve sufficient volumes at the expense of the brand holder’s image and positioning. Can investing considerable amounts into a product that is more likely to fail than succeed and that, if it were to succeed, may only generate measly returns, be justified? Does the sector need to change its approach?

Making sense of what is going on in this sector is a challenge and every strategy under the sun has been tried with varying success. Over the past decade a number of trends have begun to emerge, which we propose to review below.

Product – ditching the face in favour of the nose

The perfumer (or “nose”) as opposed to the celebrity is beginning to take centre-stage. Niche brands, such as Frederic Malle, which names the nose behind each of its scents, have emerged as a strong category by tapping into consumers’ demands for quality inside the bottle and a story behind the fragrance. A number of luxury houses have also brought noses in-house to re-invigorate their fragrance business and develop a more coherent fragrance offering. Whilst noses have always been behind the creation of a fragrance, the brief they are given seems to have changed dramatically from one that is quite specific and developed with the help of consumer focus groups to one where free rein is given to the nose’s experience and creativity. A number of fragrance houses have also placed more emphasis on the raw materials used in their perfumes; Le Labo has named each of its fragrances by the primary note used in the fragrance followed by the number of ingredients used to make up that fragrance.

Price – breaking through the glass ceiling

There has been a move to break away from the “one price fits all” paradigm that has been blighting the sector, which has both enabled and been a result of increased focus on the ingredients of a perfume. One segment in particular that has benefited from this trend is the prestige segment, which also includes niche brands; anecdotal evidence suggests that sales in this segment have been going strong even in the current recession (Harvey Nichols fine fragrance sales were up 40 % in 2008, Tom Ford’s Private blend (£250/bottle) sales have doubled at Selfridges). For those that can get away with it, this much higher pricing structure also allows brands to generate sufficient returns on their fragrance portfolio without having to resort to a high volume sales approach.

Place – making the customer feel special

Distribution has always been a thorn in the side of the fragrance industry, notably with the influence of “pile them high and sell them cheap” chains such as Beauty Base or The Perfume Shop. A lot of work has been done to redress this issue by both brands and retailers. Luxury brands have focused on reining in distribution; notably prestige fragrances are typically distributed only in the brand’s own stores and in select department stores: Chanel has gone even one step further by launching its own fragrance room on the ground floor of Selfridges Oxford Street. A number of niche brands only distribute their fragrance through their own stores or dedicated concessions (staffed by their own employees) in department stores. Le Labo takes this one step further and actually mixes its fragrances for the customer on the spot in its stores and concessions. A number of department stores have also upped the stakes in their fragrance department, improving merchandising (notably by dedicating more space to prestige and niche fragrances) and staff training, and as a result are agreeing a larger number of exclusive distribution deals for longer periods.

Promotion – turning the volume down from a shout to an interactive murmur

Whilst it still plays an important role, advertising has lost its prominence as THE tool to launch a fragrance. Prestige fragrances and niche brands have eschewed this form of communication in favour of word of mouth and interactive web-based vehicles. Notably they are tapping into the proliferation of blogs on perfumes (NowSmellThis for instance has 10,000 hits per day) inviting bloggers to fragrance launches and, in some cases have even set up their own blog. Whilst this alternative form of communication is not free, it is cheaper than advertising and very effective in garnering long term support for a brand.

In early 2000 Hermès made public its concerns over the relevance of its fragrance business; the company opted for a thorough review of the division and implemented a number of changes as follows. It hired a nose, Jean Claude Ellena, in 2003 giving him a high degree of creative freedom. The fragrance collection was segmented into three tiers, with a new prestige range (Hermessences) being launched in 2004 and distributed exclusively in Hermès stores, a fine fragrance range (Jardin – tied in with the annual themes of the brand) being distributed in Hermès stores as well as selected department stores and specialist retailers, and “window” fragrances based on the heritage of the brand (eg: “Kelly Calèche”) and designed to provide an access point to the brand by distributed more widely. The first two categories are not supported by advertising campaigns, whilst the third is. The division has emerged into being one of the fastest growing business areas of the company in 2007/8 with sales of Eur119 million.

The product should sell the brand just as the brand should sell the product

We cannot profess to give guidance as to how to develop and launch a successful fragrance: this is an increasingly challenging sector which should be approached with great caution. What we have seen is that the temptation to make quick money on the back of a brand can often come back and haunt a brand owner. For a fragrance to work in the long term, it needs to make sense and be able to stand alone as a product in its own right within a brand’ s universe. This requires developing a product that is truly in keeping with the underlying brand both in terms of scent and quality of ingredients. It is also critical to engage the consumer on all levels, especially at the point of purchase, and to create an on-going rapport between the actual product and the consumer.

Japan falls from grace as brands turn to China

Over the last year or two a barrage of articles have been flooding publications all over the world about the state of the luxury goods market in Japan. In June this year, the Financial Times went as far as to declare, ‘Japanese fall out of love with luxury’. The conjecture vis-à-vis Japan’s ‘mysterious’ turn away from excessive consumer expenditure culminated with the recent news that Versace are to pull out of the country that was ‘once the world’s most reliable buyer of all things foreign and expensive’ . LVMH also added fuel to the fire by announcing that they were calling a halt to their planned store opening in the country’s capital after having witnessed sales in the region drop by 20 percent in the first half of 2009. All eyes are now firmly fixed on China. Admittedly this is hardly a new and note-worthy topic; Savigny Partners investigated the downturn in luxury spending and change in consumer attitudes in Japan three years ago, at a time when China was starting to appear on the map for most luxury brands. Since then the road to China has become frenzied, and it seems appropriate to draw some parallels between the Japanese experience of a maturing market and the new darling of the luxury sector.

China’s little emperors are more individualistic than their Japanese counterparts

While individualism isn’t necessarily a concept that one automatically equates with the Chinese people – who have traditionally stood by the collectivist spirit promoted since the rise of communist rule, it now appears that the rapid pace of change within the country has also fostered a new generation that is empathically opposed to the ideas that their parents still hold so dear. The little emperor syndrome that was born out of the one-child policy can certainly be held, at least in part, accountable for this transformation in attitudes, with a generation of youth all believing that they hold a special place in the world. A KPMG survey in 2007 reported that on average over 60% of people used luxury goods as a demonstration of status and success compared to less than 20% who consumed them in order to fit in. This contrasts starkly with the more group-orientated Japanese culture where decisions are traditionally made by consensus, and one’s peer group is looked to for feedback and acceptance. With an urban population that are looking to express themselves as individuals it is possible that China’s spending patterns will change more quickly than they have done in Japan, to one similar to the ‘Prada Primark phenomenon’ that is commonplace in mature luxury markets where consumers are happy to mix and match brands and price points.

Brand loyalty is in Japan’s DNA

Japan is a culture that is uniquely loyal; it is one of the few countries in the world where one expects to keep a job for life. This loyalty extends also to the brands that they buy into and is unlikely to be replicated in China, a country of people who are ethnologically very different in this regard: brand-hopping in their mission to seek out of the next product or collection. So, could it be that the cult of the LV bag, that is still to this day a compulsory item in Japan, will not have the same longevity in a China whose population is already proving to be less brand loyal? While Japan’ s reliable devotion is almost certainly inimitable, the fact that 80% of Chinese luxury goods consumers fall under the age of 45 (a figure that contrasts dramatically with the demographics of consumers in this sector throughout the Western world) does give brands hope that they will have the opportunity to shape consumers tastes and spending habits and to build loyalty.

In spite of the Chinese insatiable desire for the latest fashions, big luxury brands are currently having a ball in China catering to a hungry, unsophisticated customer base. The market will mature and this will not always be so. While enriching the client relationship with a view to create a sense of ownership and to foster customer loyalty is the conundrum luxury brands now have to solve everywhere, nowhere it is as important as in China, the Eldorado of luxury goods, where the stakes are so high and brand loyalty is, well… to be tested.

From cultural revolution to cultural promotion

The ‘tsunami of Westernisation’ in the decade-long build-up to the 2008 Olympic games certainly helped the campaign of luxury goods companies, bringing with it not only a new awareness and interest in Western culture as well as the inevitable desire to own anything logo-ified, but also Western style shopping malls. However, the Olympics were also an opportunity for the Chinese government to parade both to its own people as well as to the rest of the world not only what China had to offer, but that it had arrived and was here to stay. This resurgence in national spirit meant that the tide of westernisation has been somewhat curbed in favour of a rediscovery of Chinese culture. So in terms of national confidence China is in a completely different situation to that of post-war Japan, who emerged from the period of occupation inexorably linked to the United States and its cultural influences. Looking at the early collections of Japanese designers Issey Miyake, Kenzo and Yohji Yamamoto where much of their work imitated the work of Western designers, this lack of cultural confidence is evident. Furthermore as Chadha and Husband explain in their book The Cult of the Luxury Brand, none of these designers were to gain a following at home before they were accepted by the rest of the world. In contrast, the recent, well-publicised huge military parade on Tiananmen Square to celebrate sixty years of communist rule was certainly not short of self-confidence!

It has often been stated that luxury goods transcend the notion of cultural nationalism, and it is easy to perceive the current Chinese admiration for Western brands and specifically for brands that are successful on a world stage. However, the growing interest in their own culture might very well lead the Chinese consumer to look for something that is more uniquely Chinese, and in our view this will happen more quickly than it has in Japan, where a similar phenomenon is still relatively new.

The land of the rising brands

When we travelled to China at the end of 2006, we were surprised to find out that Chinese businessmen and entrepreneurs were actually more focused on developing Chinese brands than buying Western brands. This has the backing of central government, which is championing Chinese creativity and has invested heavily in fashion design education at university level. There is definitely a wind of sinicization in the luxury sector, much as it blew through the contemporary art market over the last few years. It is compelling that Christian Bédat, the Swiss entrepreneur and founder of the eponymous watch brand, chose to name his latest web-based watch venture Red8!

Chadha and H usband assert that ‘with the economic ascendancy of Asia… its cultural impact will increase too’, and indeed, the Chinese are extremely zealous about the export of their culture. The number of Chinese Studies courses and centres rapidly increasing year-on-year at universities around the world, and with an estimated five hundred schools in the UK offering Chinese as part of their curriculum to pupils aged eleven and upwards, the next generation of potential luxury consumers are already being immersed in the culture of the Middle Kingdom.

As Savigny Partners prepares to invite Ports Design Ltd into the SLI , we look forward with excitement to further developments in China, not just as a consumer of luxury goods but also as a growing influence over the luxury sector as a whole.

Ports Design to join the SLI!

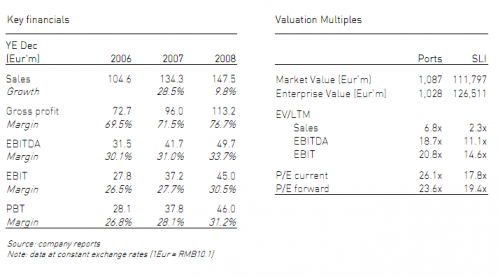

We are very impressed with the success that the Chan family, originally contract manufacturers in Canada, has achieved in building Ports, a Canadian apparel brand, into one of the leading luxury brands in China. The Ports brand, originally founded in 1961 in Toronto, has been successfully transitioned from a largely North American retailer to an international fashion company with one of the leading positions in the luxury segment in mainland China, supported by an extensive retail network in the country.

Ports was acquired by the Chan family in 1989. In 1993, the brand was introduced to China with two initial stores opened in Xiamen and Shanghai. In the first five years of operations, the company opened over a hundred stores in most of the larger cities in China. Today Ports is sold in over three hundred and seventy shops, ranging from concessions to flagship stores, in over sixty cities.

Beyond the numbers, here is a fact to be reckoned with: Ports was voted in 2007 by Vogue readers in China the second most desirable luxury brand after Chanel, and was placed again as one of the top five international luxury brands desired by young mainland consumers in a survey conducted in 2008 by AC Nielsen. It is consistently recognised by Chinese consumers as being one of the top three or five most desirable international brands, despite price points being lower than those of imported Western luxury brands.

This has been achieved on the basis of a vertically-integrated model, with in-house design, manufacturing, marketing, distribution and retail functions. In a nutshell, the current ownership team has achieved production of international quality (for both tangible and intangible products) on a Chinese cost base, with the reward that the group’ s PBT margin is now above thirty percent. Other businesses include the license to design, manufacture and distribute fashion products and accessories under the BMW Lifestyle name in China (the company operates over forty BMW Lifestyle retail outlets) , a recent joint venture with Vivienne Tam, and distribution agreements with Ferrari and Giorgio Armani. In addition, the group has a small OEM business which exports merchandise to major retailers in North America and a wholesale business for BMW Lifestyle and Ports branded clothing.

The group also launched a new upscale line, Ports 1961, in 2003 in New York, with a separate design team and higher price points than its sister brand, Ports International (Ports Design Limited, the listed company, controls the rights to distribute and market the Ports brand, including Ports 1961, throughout Asia whereas the private parent company of Ports Design owns the rights to distribute and market the brand in Europe and the Americas). Ports 1961 now has over eighty points of sale globally, and is available in the United States, Canada, Japan, Dubai, Hong Kong as well as China. The group also operates five directly-owned stores in North America, with a flagship location in the heart of the Meatpacking District in New York. After the close of the Ports boutique on London’s New B ond Street in early 1990’s, the group will re-launch Ports in Europe next spring with the opening of a store on the designer floor of Harvey Nichols.

The Chan family currently owns approximately 40% of Ports Design Limited, which has a market capitalisation of over a billion euros and is listed in Hong Kong. The family also owns and operates PCD, the leading high-end department store chain in China with seventeen stores spread over nine cities, including Beijing.

All in all, our conversations with management and our understanding of their business strategy and growth prospects have convinced us that Ports Design is a good proxy for the Chinese luxury goods market, and thus merits inclusion in our SLI. This is the first time that the SLI departs from strictly European or American stock. The stock will be included in our index and valuation table starting in our next issue.

Sustainability and the Luxury Industry

Adapted from an article by Florian Gonzalez to be published in the October issue of Reflets, the magazine of ESSEC’s alumni network.

2009 is the year when the word “sustainability” officially entered the luxury professionals’ lexicon and agenda. The consequences of such a dramatic acknowledgement are far-reaching and entail a revision of every single dimension of the industry, including product development, marketing, finance, distribution or human resources. This revolution is currently taking place and will obviously slowly redefine the very notion of “luxury” together with brand identities and brand perceptions.

Luxury group shave made their “coming-out” about sustainability:

In November 2007, when the International Herald Tribune dedicated its luxury conference to “Supreme Luxury” with every brand rushing into Russia and Dubai, it was hardly predictable that, in March 2009, the same international newspaper would host a “Sustainable Luxury” conference, urging luxury brands to embrace sustainability. Now that the myth of the recession-proof luxury industry has been exposed, brand owners are revisiting their beliefs and value system as they relate to growth, profit targets and corporate culture.

At the IHT conference, Francois-Henri Pinault made a long speech which can be considered as a very encouraging and symbolic step towards sustainability. Noting that the expression “sustainable luxury” could sound like a contradiction, he considered that it was necessary to go beyond this contradiction as “growing concern for the planet and greater respect for the people all come together. Luxury and sustainable development share the same values and can support each other. There is no time for reflection or pessimism but for action. Let’s be ambitious and effective before it is too late. Luxury can and should raise awareness. ”

A few months later, at the Financial Times Summit in Monte Carlo, Bernard Arnault acknowledged the importance of sustainability in a keynote speech. In noting that the ‘luxury as usual’ momentum was over, Mr. Arnault expressed the opinion that the desire for exceptional products would survive the crisis as long as innovation and creativity lead the way. In this regard, he intends to view the growing environmental issue in the world not as a constraint but as an opportunity, and he referred to LVMH’s recent investment in Edun, a fashion company founded in 2005 “with a mission to drive sustainable employment in developing economies”. According to Mr. Arnault, a socially responsible, more demanding luxury customer is appearing to which companies will have to adapt, while preserving profitability for their shareholders.

Actions speak louder than words and sustainability experts are very cautious when it comes to corporate promises. The definition of sustainability was first minted by the Brundtland Commission in 1987. An updated definition could be: “Physical development that achieves net positive impacts during its life cycle… by increasing economic, social and ecological capital.” (J. Birkland, 2008). Unfortunately, the lack of a universal definition of sustainability leaves space for all kinds of questionable marketing practices and deceiving propaganda. Indeed, the “green-washing” temptation is strong and a company’s financial strength, together with the stability of its ownership, are probably the best guarantees for a long term commitment to such a culture shift.

Tentative guidelines to help make the luxury industry more sustainable:

Florian Gonzalez is suggesting the following guidelines to the luxury industry:

1 . Sustainability requires to revise business models and particularly to give sustainability a role in companies’ financial valuation and targets. This is part of the so-called “triple bottom line” (people, planet, profit), expanding the traditional reporting framework to take into account ecological and social performance in addition to financial performance.

2. Sustainability requires the interest alignment of all stakeholders from ownership and top management down to staff and supply chain partners.

3. Training is key and employees shall be given incentives in order to learn and achieve concrete results in terms of sustainability.

4. A sustainable business puts sustainability into its core mission, hence luxury companies shall make their products’ sustainability a priority (vs. charity work).

5. Design can be eCo-driven and not eGo-driven (Eco-design vs. Ego-design). Sustainability shall inspire new co-design and co-creative processes in the name of ‘design activism’ (Design Activism, Alastair Fuad-Luke, 2009).

6. Fast fashion should be seen for what it is most of the time: throw-away products, waste of resources and low prices obtained thanks to poor social conditions in Asian factories. Slow fashion instead means selecting, enjoying and caring products we buy: “Consume less, live more” (The 11th Hour, a documentary by Leo-nardo DiCaprio).

7. Being carbon neutral is only a first step: actually reducing carbon emissions and making a positive impact (vs. just “neutral” ) is the real name of the game.

8. Brands which consistently and constantly improve their sustainability credentials will reinforce customer loyalty and increase their customer base over time.

9. Profits made out of unsustainable businesses are nothing less than “ecological evasion”.

10. Sustainability requires a permanent learning process made of humility, generosity, kindness and sharing of knowledge. Companies should not be afraid of sharing best practices and creating positive externalities.

Finally, following philosopher Alain de Botton, it may be time to revisit our very notion of wealth: “The current economic crisis is forcing all of us to rethink nothing less than the meaning of life. In particular, it is prompting us to re-examine a key idea in our society: the connection between making money and being happy.”

Sector Review

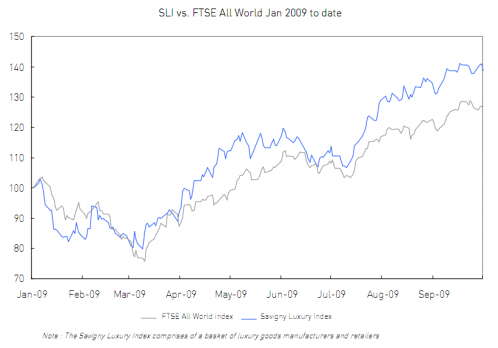

Pushing the 52 week-high higher

The SLI has rallied 22% since the publication of our last newsletter in July, partly fuelled by a general recovery in global stock markets. This was evidenced by the 14% increase in the FTSE AW over the same period, but sentiment towards the luxury goods sector has also improved resulting in the index outperforming the FTSEAW. A number of luxury stocks have hit and exceeded their 52-week highs on several occasions over the last three months, whilst the SLI hit its 52-week high twice in September. A notable riser was PPR, which hit a new 52-week high eight times in September alone.

Less un certainty and less bad news (we hope!)

The bulk of the companies in the SLI have reported half year results in the last couple of months and these have come in line or ahead of expectations. The general theme is that although we are not out of the woods yet, things are not as bad as expected. The overall feeling is that of the sector having bottomed out; some companies are even starting to see a recovery in demand, thus improving their outlook for the second half of 2009. Swatch was the first to come out with a slightly more optimistic outlook for the second half of the year; it did so in mid-July and set the ball rolling for an upward re-rating of the sector. This was followed by similarly improved, albeit cautious, messages from Tiffany, Hermès and LVMH. As a result, industry observers revised their sector sales growth estimates upwards for 2009 to a decline of 10%, relative to the forecasts of a 20% decline being bandied around at the beginning of the year. This relative optimism should however be tempered by negative reports from retail floors in August and September. Let’s hang on!