03/07/2007

Challenges of the Spa Market

With contributions from Cindy Palusamy, CP Strategy Inc.

A large and growing market

The search for the fountain of youth continues unabated in the 21 st century, best evidenced by the boom in the spa business in the past decade. Industry experts calculate annual global spa revenues north of $40 billion, inclusive of services and products. The International Spa Association recently reported that there are 1 50 million active spa goers world-wide. The sheer size of the market makes it one of the largest leisure industry segments, but with no clear leader at the helm. A broadening understanding and appreciation of alternative healing and wellness regimes by consumers coupled with the burgeoning investment in and supply of spas (mostly in hotels and resorts) has resulted in an industry growing by double digits annually over the last decade.

Hotel spas grab the lion’s share

Many of these consumers are checking into hotels on their quest for their next spa experience. While hotel spas consist of only 14% of the market in terms of units, they register about 41 % of total industry revenue (ISPA, 2005). Travel agents concur: in a survey by SpaFinder 65% of travel agents said spa bookings were up in 2006 and stated that spa facilities / access to a spa are the most important considerations when making vacation plans. Most relevant to the hotel companies is the impact on average daily rates, which some studies put at a 50% uplift for destination resorts with spas. As a result, hotel groups are investing heavily. A recent article reported that the top hotel groups (and related developers) are spending close to a half-billion dollars in the next few years on their spa facilities. Top of the list is Hilton Hotels, which has recently announced a deal with spa operator Spa Chakra, using LVMH’s Guerlain and Acqua di Parma brands within various luxury properties (Waldorf, Conrad and selected Hilton hotels). Hilton further commented that it and its property partners would invest $200 million to develop 70 new spas across its global hotel portfolio, more than doubling its current count of 65.

Day spa model has been a challenge

The largest investment to date in day spas has been by US-based private equity firm Northcastle Partners. When Northcastle acquired Red Door and the Mario Tricocci Salons, they inherited a typical day spa model with its own locations—both freestanding and in department stores. The company owned the full p&l and in turn covered capital expenditures and funded working capital. While Northcastle is not commenting on its invest- ment, Red Door has not seen growth in the number of its freestanding locations to match that of the sector as a whole. In fact, Red Door has had to adapt its business model and now operates a significant number of its locations from within hotels under management contract.

Now consider another leading spa group, cruise ships specialist Steiner Leisure. Its 2001 acquisition of the land-based Greenhouse and related day spas probably seemed attractive as a way to quickly build a proprietary distribution platform for its Elemis product line and leverage its longstanding expertise in cruise ship spa operations. However a ship business, with a captive audience and relatively little off-peak times, is vastly different to a day spa business, requiring substantial customer acquisition and retention costs. The acquisition proved disastrous and Steiner was quick enough to exit the day spa business at a significant loss. Steiner has since seen record double-digit growth, fuelled both by services as well as the spectacular success of the Elemis product line, which is now a $100 million plus global spa brand also distributed wholesale in non-spa channels.

Renewed interest in spa distribution channel by beauty manufacturers

Along with interest by hotels, there seems to be renewed interest in spas from leading beauty manufacturers, after an unsuccessful foray in the 1980s and 1990s. Estée Lauder opened and subsequently closed Lauder spas in the late 1990s: opened mostly as concessions in department stores, the spas never fully realised their potential. L’Oréal opened and closed Helena Rubenstein spas within a couple of years but has remained in the spa business via product lines.

LVMH acquired and sold Bliss over the course of five years, although their heart was probably more in the brand potential than in the spa business itself. Shiseido owns one of the largest spa skincare brands globally, Decléor, but has focused on purely being a supplier to the industry.

Recent announcements by various hotels on future investments in the spa sector bode well for beauty manufacturers as a distribution channel. Historically, the biggest drawback for such companies to service the spa sector has been low volume opportunities as a result of a fragmented customer base. As global hotel companies take a more strategic and centralised view towards the business, more significant and “deliverable” opportunities for cosmetic brands are arising.

Not all spas are equal

Amongst the challenges facing the business lies a classic identity crisis. The use of the word “spa” has come to mean everything from three-room day spas to 40-room megaspas to doctor-led medispas. The differences between the various formats are considerable. Successful day spas require private-label brands (70%+ margins) and a strong local, repeat business to survive. Hotel spas require strong links to hotel reservations and marketing programs to ensure consistent guest usage.

Geographical differences further complicate matters. Western market spas derive value from product and benefit greatly from hosted environments (hotels, retailers, etc) to subsidise upfront capital expenditures. Developing market spas – where there are real growth opportunities – derive value from service due to low labour costs and benefit from captive affluent audiences accustomed to paying a significant premium for spa services.

All told, the industry’s basic classification system and available statistics have failed to capture the true picture of the market. Interested participants need to look at the business with a far more detailed eye. Restaurants serve as an interesting comparison. The highly fragmented restaurant business is quite similar in cost structure to spas. The restaurant industry does not however classify itself along location (cruise ship, hotel, etc.). Rather, the industry has defined itself along a matrix of price and volume. High price and low volume food establishments generally equal fine dining establishments. Low price and high volume equals fast food. The same can be applied to spas. Some spas focus on quick treatments and focus on volume. Others are five-star service, low volume and high prices. Mixing the two together to draw conclusions is the equivalent of lumping McDonald’s and Ducasse into one category.

Similarly, the industry has given little thought to yield management. A key lesson from the airline industry is that the value of a product (i.e. airline seat) changes as a function of time and day. The same holds true for spas: a treatment on a weekend or after work is more valuable than a treatment mid-morning on a weekday. Spa owners need to develop effective pricing strategies to ensure revenue optimisation.

The spa market will likely remain at the forefront of discussion as opportunistic investors seek to bring some order to this growing industry. No clear leader has emerged with the right formula for success. Until then, our money will be on “bundled” groups, where good locations meet good operators meet good brands, as with the recently announced Hilton / Spa Chakra / LVMH deal.

Gold rush or long term investment?

From the press commentary and the increasing frequency of launch parties in Mumbai and Delhi, it would seem that India cannot get enough of luxury brands. Latest to stake its interest, Hermès has just announced it established a joint venture company to open stores in India, with a first unit expected in New Delhi. Many analysts indeed view India as the next untapped big market opportunity after Russia and China.

The India consumer growth story is well established: forecast GDP growth of 8% p.a. for the next ten years, with projected growth rates in the “sheer rich” to “super rich” category (annual income above $100,000) set to average at 25% p.a. over the next five years to over 500,000 households. The organised retail market is set to explode, from less than 5% of the current estimated $12 billion value of total retail spending to an estimated $25 billion in five years according to some surveys, driven by an unprecedented construction boom for in-town and out-of-town malls led by India’s most successful industrial groups including Reliance Industries, Bharti, Tata Group, ITC and Birla. Amongst many projections, Deutsche Bank estimates that, over the next three years, 600 new shopping centres will be developed in India.

Our concern is that much of the hype about organised retail sales growth is based on a number of self-reinforcing “chicken and egg” assumptions, and that the reality will be somewhat less than anticipated. Retailers often cite the rate of mall construction to support their total sales projections, and developers cite the projections of retailers to justify the investment being made in mall construction. A simple walk around Mumbai’s leading modern format mall, called Inorbit, suggests that the supply of sophisticated retail facilities does not automatically translate into product demand and strong retail sales (with the exception of the food court, which is packed). This is all the more telling as Inorbit continues to enjoy ‘novelty’ appeal and no meaningful competition.

The implications of similar assumptions being made in the luxury end of the market are potentially far more serious. Projections of growth in disposable incomes and the absolute number of ‘super-rich’ appear to have facilitated a simplistic approach to corporate decision making. When it comes to market entry decisions being taken by some luxury brands, it seems to be more ‘Field of Dreams’ (if you build it they will come), than decisions based on a clear understanding of the nature and challenges of the market.

Barriers to entry remain

A restrictive regulatory environment, the cost and availability of appropriate infrastructure, the lack of brand awareness and the very limited media outlets for marketing make establishing a successful luxury brand business model in India considerably more challenging than might first appear. Added to this, the potentially underestimated price consciousness of an emerging consumer class brings into question the widely held assumption that India is about to embark on a branded luxury goods spending spree from Armani to Zegna and a little bit of La Perla and Mont Blanc in between.

India remains a largely protected market with respect to foreign entrants, partly in order to afford Indian businesses time to establish a competitive platform before the market is opened to global powerhouses. Multi-brand retailers have to operate through franchisees and license agreements whilst mono-brand retailers can own up to 51% of their businesses in India.

Aggregate duties on imported luxury products are prohibitive: up to 35% on apparel, 45% on accessories, 60% on watches, shoes and perfume, all augmented by interstate duties (in some cases 8%) and VAT of 12.5%. Given that the wealthy Indian elite targeted at pre-sent by luxury brands is likely to be well travelled, the incentive to buy locally is not only diminished by the significant price premium but, arguably, also by the diminished cachet of buying a $3,000 bag at the local mall instead of, say, Bond Street.

Last but not least, the infrastructure necessary to support a commercially viable luxury brand development strategy in India is largely lacking. In spite of isolated examples of investment such as DLF’s Emporio in Delhi, the reality is that there is no retail infrastructure in India that can be compared to developments in other fast emerging markets in Asia, the Middle East or Russia, let alone Europe and the US. With the possible exception of LVMH which has the critical mass to drive a largely independent positional strategy should it wish, most luxury brands are opting for India’s premier hotels as a location solution out of necessity rather than choice. The problem with this is two-fold: firstly, the strategy in India mostly international business clientele of those hotels does little to enhance sales to wealthy locals and, secondly, the cost of such retail space is usually prohibitive, both in absolute terms and as a percentage of sales.

The belief in the benefits of local partnership can be misplaced

The numerous challenges facing new market entrants have limited the preferred route of many international luxury brands and forced the alternative of either a joint venture with a passive or active partner or, as in most cases to date, a licensing or distribution agreement. Such joint ventures and license agreements will face substantial challenges. At the heart of those challenges will be the misalignment of economic expectations between the local partner and the luxury brand as well as the lack of genuine brand experience of the majority of potential partners in India.

International luxury brands may well view their entry into India as a long term strategy with a justification based more on brand building and the wallet of the international Indian, rather than expectations of meaningful returns from the local operation. However, large Indian retailers and local business promoters, who are striving to be the local partner to international luxury brands are arming themselves with inevitably optimistic sales projections and building substantial businesses out of nothing, with very significant license acquisition, real estate, fit-out, inventory, duties and salary costs, all of which are committed largely in advance. It is unlikely that most local partners or licensees in India will generate a positive return on their investment in the expected timeframe.

Whilst misjudging sales may not be directly meaningful for the brand owner, it can be hugely so for the local partner. The particular concern here is that the local partner might in turn attempt to improve its return by cutting costs where it can; more often than not this means marketing and brand development.

Zegna learnt this lesson the hard way. The company initially opened a licensed outlet at Mumbai’s then leading mall in 2000. In spite of the positioning and expectation at the time the store closed, not so much because of disappointing sales, but because of the adverse impact on the brand positioning due to a deterioration of the brand environment, which included a McDonald’s restaurant opening next door. The company has just reopened as a majority owned business in the Taj Hotel. Whilst Zegna’s near term earnings will be impacted by the cost of space at the Taj, they can control a long term brand building strategy based on appropriate pricing and control of their environment rather than be driven by the shorter term economic requirements of a local partner.

The long term opportunity for luxury brands in India is substantial. However the near term risk of potentially dysfunctional, brand-eroding partnerships and license agreements will compromise more than just near term financial returns. The lesson of Zegna, as for others, is to commit fully both in management time and money to build for the long term and accept that there is no short cut or low cost way to build a high value luxury brand in India. The alternative would be to spend a fraction of the money that it would cost to establish a retail infrastructure in India on an advertising campaign that builds brand awareness amongst a sophisticated and increasingly affluent and cosmopolitan Indian population. With the number of distribution and licensing partnerships which have been announced over the last couple of years, it seems that the majority of international luxury brands are taking a middle ground approach which many might regret.

Luxury Brands and the Internet – From Laggards to Leaders?

Internet sales of luxury products are booming and brands are joining in

Sales of luxury products on the internet are booming. Forrester Research estimated global internet sales of luxury goods to be $3.2 billion in 2005, a 28% increase on 2004.

Pioneers such as multiple brand retailers Neiman Marcus and Nordstrom as well as specialist sites Net-à-Porter, which posted a 75% sales increase in 2006, and eLUXURY.com have paved the way for luxury brands. Over the last couple of years, leading brands such as Louis Vuitton, Hermès, Dior, Gucci, DeBeers and Bottega Veneta have rolled out dedicated transactional websites. Louis Vuitton, based on the success of its online boutique on eLUXURY.com in the USA, opened a transactional website in France in autumn 2005. Dior’s site, launched initially in France in autumn 2005 and now transactional in the UK, Italy, Spain and Germany, already achieves sales comparable to one of its largest boutiques. Hermès’s US site, opened in 2002, is the second largest sales channel for the brand’s silk ties in the USA.

The question is why now and why did it take the luxury sector so long?

A better understanding of the internet audience

Luxury brands were initially reluctant to establish a web presence principally owing to concerns that such widespread distribution, be it in the form of a purely informational site or transactional site, would dilute the brand’s image by making it accessible to a too wide or inappropriate audience. This perception was reinforced by the proliferation of “bargain” websites, such as Lastminute.com and eBay. The internet appeared to be the destination of choice for the ultimate bargain experience, rather than the ultimate shopping experience luxury brands strived to convey.

That negative perception was shattered when luxury goods bosses realised how much business Neiman Marcus, Bergdorf Goodman and Saks were doing online, and saw the success of Net-à-Porter. Recent surveys also help paint a different picture. New York- based Luxury Institute found that 96% of Americans with annual incomes of $150,000+ buy products and services online, and that 99% use the internet to research before they buy. These findings were reflected in a similar study conducted in France, which also found that people in lower income brackets were less likely to buy products online.

Cannibalisation of sales or access to new markets and customers?

Another reason cited for eschewing the internet as a channel of distribution was the fear it would cannibalise sales of luxury brands’ own stores or those of their distribution partners.

The success of transactional luxury websites in the USA has shed a new light on this matter. The internet has enabled luxury brands to cost-effectively reach target audiences in markets unable to support a bricks and mortar retail presence. Information gathered from web sales has also enabled companies to identify regions/states, such as North Carolina, with sufficient demand for luxury products to justify investing in a store. Fur- thermore, customers in luxury goods’ primary markets that are either cash rich/time poor or too intimidated by the exclusive boutique environment are ideally suited to the internet. Nordstrom’s website has emerged as the chain’s “biggest door”, generating $530 million in sales in 2006 and forecast to reach $1 billion within three to five years. The company claims that multi-channel customers shop four times more than the customer who shops one channel, justifying its heavy investment in its website as a complement to its bricks and mortar business.

Missing out on the brand experience?

Having invested heavily in the development of monumental flagships in the 1990’s, luxury brands found initially that the technology behind the internet was insufficient to translate the brand experience from the store to the web.

The advent of broadband, along with flash graphics and audio-visual capability, liberated

the creative potential of the internet, allowing brands to present their collections in an appropriate setting. Better resolution and the possibility to zoom in on product features, examine them from different angles and, in the case of apparel, on different body shapes also facilitated and enhanced the shopping experience. Websites are now working hard to create a special environment, add editorial content and improve customer service.

Bergdorfgoodman.com not only shows the latest Theory collection but has a ”Ways to Wear Theory” page showing how different pieces can be combined into outfits. Neiman-marcus.com has gone one step further, partnering up with In Style magazine to create an “Instant Style” section in which shoppers can put together ensembles. Net-à-Porter’s homepage and its “what’s new” and “magazine” pages read like a high quality fashion glossy.

The WEB2.0 generation: tomorrow’s customer, today’s challenge

The next generation of luxury goods consumers has been brought up on a diet of social networking sites (SNS), such as MySpace and Facebook, blogging and interactive new media sites, such as YouTube and Joost. This generation presents both a challenge and an opportunity for luxury goods brands.

The challenge is to reach this audience, which has largely turned its back on traditional media. The signs are already there in the current generation of luxury consumers. The Luxury Institute found that, whilst 73% of wealthy Americans said that internet presence improved their perception of a company and 30% of those surveyed found ads on internet search engine sites to be an effective marketing technique, only 10% found ads in traditional media effective. Some brands are beginning to pick up on this trend. Fendi launched a “buzz” campaign in Japan to launch its B Mix leather accessories, Armani broadcast its Paris show on MSN online with video excerpts sent to Cingular phones, and Dior launched four pieces of its latest jewellery collection on the virtual digital world of Second Life. Sources in the advertising industry estimate luxury brands will spend c.8% of their communications budget on the web in the near term. This figure is likely to increase as the new media universe matures. The emergence of dedicated new media channels, such as luxe.tv and fashion.tv, will not only allow luxury brands to access their target audiences effectively but also in a more controlled environment than generalist sites.

The opportunity for luxury brands lies in using the web’s SNS features to foster a community spirit around them. A platform where customers and fans of the brand are able to communicate not only with the brand but amongst themselves (in an appropriate, monitored environment) will increase their sense of ownership in the brand and their loyalty. Additionally, by encouraging feedback from customers in this manner, luxury brands will be able to gain valuable insight into perceptions of the brand, its products and services.

Whilst luxury brands’ initial reticence towards the internet has been overcome and significant steps have been taken by some in the right direction, the potential of the internet has yet to be fully realised. The rewards are likely to be significant for those who stay ahead of the game.

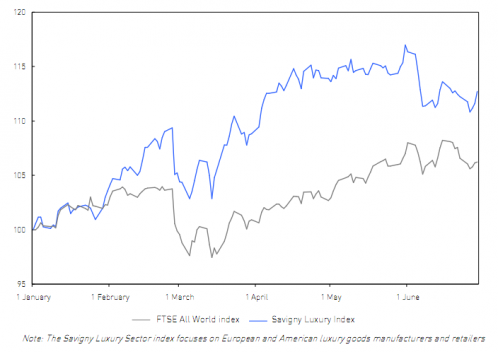

Savigny Luxury Index vs. FTSE ALL World

During the first half of the year the Savigny Luxury Index (SLI) continued its strong progression started a year ago, increasing by 12.7% and outperform ing the FTSE All World Index by more than 6 percentage points. Year-on-year the SLI has risen by approximately 40%, or about double the increase of the FTSE All World! However this sterling performance masks some recent uneasiness, which came through in the last couple of months.

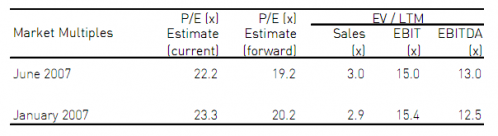

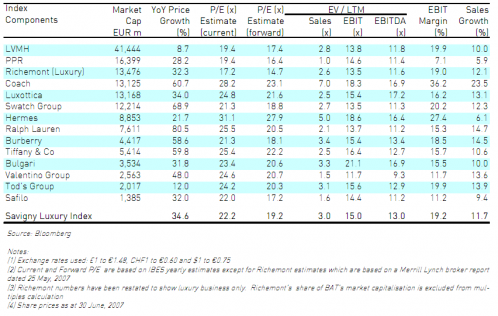

The sector had a bull run, but valuation multiples are holding up

No question, it is fair to talk about a bull run on luxury goods stocks since the middle of last year, which actually coincided with the lowest point of the year for equity markets globally. At first glance, this may raise doubts as to inflated valuation in the sector. We recently raised som e concerns about Japan being flat and the worrying effects of currency fluctuation, namely the continued drift of the dollar. A closer look at valuation multiples since our first newsletter show that these have in fact remained relatively stable, reflecting the solid financial performance of key luxury goods companies. We do not see cause for alarm, and believe that stock market values in the sector will hold up.

The music stopped mid-April

Taking aside the China-induced drop which took place in June (caused by a tripling of stamp duties on share transactions) and the subsequent partial recovery, the values of luxury goods stocks have remained relatively flat since mid-April. This contrasts with the steady growth in the FTSE All World Index (also affected in June but to a lesser extent), which clawed back approximately 4 percentage points in the growth differential with the SLI since the beginning of May.

The table below compares today’s valuation multiples of the stocks composing the SLI, with those computed for our first newsletter (Richemont multiples are restated in order to focus on its core luxury component). Multiples have remained substantially unchanged, in spite of the 13% increase in the SLI.